God’s own pioneers

Ilya U. Topper

Note: The author has lived three weeks in Kedumim under the identity of a German volunteer. All names are authentic, save in the sections “Immigrants” and Love between the guns”, where they have been changed as to protect the affected.

It’s a clear morning in Kedumim. A few men step out of the synagogue, get off their white prayer blankets and the black leather strips on their forearms and fix their guns in the holster. What they never would take off is the kippa, the small skullcap you need to enter a Jewish sanctuary. In Kedumim it is something more: a symbol. It identifies the settlers who are willing to keep with all means their grip on a land which to them is an indivisible part of Greater Israel.

Kedumim is one of around 150 Jewish settlements spread over West Bank and Gaza. Built on a strategic hilltop about 7 miles off Nablus, the most important Palestinian city north of Jerusalem, Kedumim is home to around 600 families or 2.500 people. Most of them settle here for a single reason: to occupy enough land as to prevent Palestinians to build a proper state. A coloured flyer signed by the settlement’s major Daniella Weiss is clear about that: “We remain the single most efficient obstacle to Palestinian ambitions”, it claims proudly.

“When expanding the settlement, we choose a distant hillside in order to encompass as much land as possible”

One of the closest co-workers of Daniella, Raphaella Segal, explains that further: “Each time we expand the settlement, we choose a distant hillside in order to encompass as much land as possible”. They don’t wait for a permission to build. “First we expanded to distant neighborhoods and then, when permission came, we began building within the perimeter”, the flyer written by Segal quotes Daniella Weiss. 48-year-old Raphaella Segal works as an oculist in Tel Aviv and is the mother of nine children. She was born in South Africa, arrived as a child in Israel and was one of the first ‘pioneers’ who occupied, in 1975, the barren hilltop of Kedumim which was to be converted into a lovely orchard.

That is, at least, the official version. The number of olive trees which had been cut down does not appear in the statistics. Neither does the huge amount of water used every day to keep garden, grass and trees blooming – six times more than what a Palestinian village would use. “It was hard times” Raphaella remembers. “We lived piled together, with no electricity, but we managed to change Israel’s map and the Jewish History. We created facts on the ground”. Now, she lives in a two-floored house with a garden.

God signed the contract

30-years-old Amit Reilinger, is proud of his thick beard and the long ‘peyot’ curls which tangle down from his temples to certify his orthodox devotion. He is one of the new ‘pioneers’. Reilinger is building his own house in Har Khemed, a hilltop one mile west from Kedumim. On a clear day, you may catch a glimpse of the sea from this point. Four housing containers shelter under a military watchtower which is manned by young Israeli soldiers.

“This is my land” assures Amit Reilinger. “Our Father Abraham bought it three thousand years ago”

“This is my land” assures Amit Reilinger. “Our Father Abraham bought it three thousand years ago”. It’s not his family who taught him this view of History. Amit’s grandparents were German Jews and engaged in the Zionist student’s movement with the aim of building a secular state with no rabbies nor prayers. Amit broke up with his family when he turned to the orthodox faith.

Faith is important in Kedumim. On saturday, no vehicle may be driven, excepting the patrol cars. No electricity may be switched on, not even a phone picked up. Light is burning since friday evening and meals are kept hot in a special stove. In the kitchen, two sinks, two sets of pots and two towels are used as to keep separate every single crumb of meat and lactic food.

“That is the way Thora shows us to live” says 40-year-old Boaz Weinreb, while he prepares the Kiddush, the sabbath ceremony, pouring grape juice into a silver cup. Boaz wouldn’t touch his breakfast without first putting the little prayer-book on the table and he shows up every morning in the synagogue. He is very attached to his job of keeping clean the schools and kindergartens of the settlement but he is happy to accept the help of a German volunteer who has come to Kedumim searching his Jewish roots – he obviously doesn’t suspect that the young man is a journalist.

Boaz is a wonderful father who never has a bad word for his ten children even if they hang all around his arms or try to disrupt his prayers. But when a new Palestinian suicide attack in Jerusalem is broadcasted, his face changes quite suddenly. “You can’t speak to animals” he mumbles. “We must attack them, it’s our only way of defense”. He never takes off the small gun in his belt and the long rifle on the back seat of this car has a telescopic sight.

Wild West Scenery

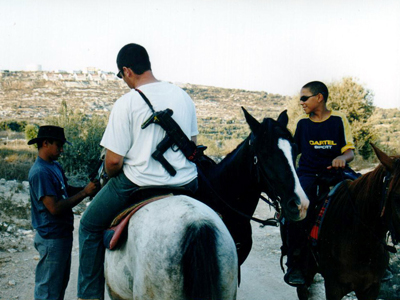

Amichai, Nitai and Uzi wear their short Israeli machine guns slung over their shoulders when they patrol the settlement on horseback. Amichai and Nitai are around twenty, Uzi, an Ethiopian boy, is hardly fifteen. There are no fences around Kedumim. “We don’t need them” says Amichai.

The real reason for this apparent lack of caution can be discovered when reading Raphaella Segal’s flyers: “Fences could be used in the future to restrict the growth of the settlement. Since the early days of Zionism, borders have been determined by the last house on the outskirts of the community”. With this strategy in mind, the major Daniella Weiss has just created a new outpost, called Gilad, around one mile east of Kedumim at a crossroad. Two housing containers, a shadow roof and a lot of Israeli flags, that’s all.

«After the clashes in Nablus, the settlers of Jitzhar went to an Arab village to burn down the Mosque»

Two regular soldiers guard the spot and a few teenagers from Kedumim turn up now and then to offer them company. The name honours Gilad Zar, the security officer of the Samaria Regional Council of settlers, who was gunned down on this spot on May 29th, 2001. Now, the nearby Palestinian village Jit has been trapped between Gilad, Kedumim and the newly built Mitzpe Yichai settlement on the other side of the road, where 200 new houses are just being constructed. It will be difficult to find enough people to live there, but when so much is talked about freezing the settlement building activities, Mitzpe Yichai shows proudly the opposition to any peace process.

From Gilad you can take the road to Jitzhar, a very small settlement pitched upon the top of one of the highest hills in West Bank. Jitzhar is famous for the violence of its settlers. “They’re fanatics” says Alicia Lev showing no emotion. “After the clashes around Joseph’s tumb in Nablus, the settlers of Jitzhar went during the night down to the Arab village Hawara to burn down the Mosque. They also use to burn the olive trees. No Arabs are allowed to enter the settlement. Not too long ago, one went there to ask for a lost horse. They knocked him down and threw his car into a ravine. Another man showed up with a photo camera. He also was knocked down”.

Alicia Lev is 23 years old, fair-haired and she speaks five languages.She was raised in Germany until her fifteenth birthday, later her father, who had Israeli parents, decided to search his roots in the orthodox Jewish faith. “We first went to live near Tel Aviv, but people there don’t comply with the religious rules” says Alicia. “So we came to Kedumim, but my father didn’t like the Arabs entering the settlement, and finally we moved on to Jitzhar”.

Statistics of Violence

Near Jitzhar, three young men are hammering on the nails of a palisade. A fourth one, with long, blond hair, watches out with a machine-gun in his hands. I try to identify myself as a German volunteer coming from Kedumim but nobody would listen to me and I’m driven back by rather unfriendly and quite loud words, trying to imagine what could have happened to me if I had a Palestinian’s face. Jitzhar also lacks fences. The settlement is well enough protected by the violent character of its inhabitants which is certified by the belt of burnt olive trees around the hill.

Jitzhar is no exception, but is at the top of the list in in the violence statistics of West Bank. The monthly Settler’s Report of the Israeli-Palestinian NGO Alternative Information Center gives all the details: “May 27th, 2001: Settlers attacked the agricultural land belonging to Sura village in the Nablus area cutting down 500 trees… A group of settlers from Yizhar opened fire on Palestinians, seriously injuring two boys, aged 15 and 16, who were shepherding their goats. May 28th: Several settlers set fire on 1.200 trees near Jenin. May 31st: Settlers from Qedumim closed the main road between Qalqiliya and Nablus. They gathered at the Jit junction throwing stones at cars without any interference from the IDF soldiers. 3 cars had their windows broken…”

In short: in only thirty days, more than 80 hectars of fields were burnt, 1.800 trees, mostly olive trees, were cut down or burnt, 2 Palestinians died when hit by settler’s cars and 58 were injured by shots or stones. A regular month in West Bank. The responsibles of these crimes are nearly never brought to justice.

Despite of the Oslo Agreements, the number of settlers went on growing over the last ten years. There were hardly a thousand in the early eighties and not much more than hundred thousand in 1993. Today there number is around 200.000. This does not include the 180.000 Israelis who live in the Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem, which are as illegally built, according to international law, as the settlements in West Bank and Gaza. The total number of settlements is estimated from 145 to 190, depending on the sources.

The ‘Oslo Crime’

Even after the Labour Party’s candidate Ehud Barak – who was expected to implement the Oslo Accords and to freeze the settlement activity – came to government, around 2.000 houses have been built every year. The Government supports this activity which is not only given military protection but also generous funding. In 1997, 300 million US dollars of the State’s budget were assigned to settlement’s development. Even so, Barak’s proposal to annex the nearest settlements to Israel and to evacuate the isolated ones stirred the settler’s anger.

The stickers on many of Kedumim’s cars read «No Arabs – No Attacks» or “Kahane was right»

Alicia Lev has no doubts: “If the Government ever tries to evacuate Jitzhar, we would come to a Civil War. They would never go”. A sticker on many of Kedumim’s cars confirms that view: “Bring Oslo Criminals to Trial”. Others just say “No Arabs – No Attacks” or even “Kahane was right”, Meir Kahane being a rabbi who suggested the complete expulsion of all ‘Arabs’ from Israeli territory. His organization Kach was declared terrorist by the Israeli Parliament since it defended the massacre of its member Baruch Goldstein who in 1994 shot and killed around thirty Palestinians inside a Hebron Mosque.

In Hebron, you will walk on bullets with every single step. Hebron is a strange city when described in figures: around 400 settlers rule over a strip of the old town while 7.000 Israeli soldiers protect them against 20.000 Palestinian civilians who live in the same part. There is a continous curfew only lifted a few hours every day. A small incident is enough to shut down the shops and to leave the streets empty and the inhabitants with no access to food or medicaments. The speaker of Hebron settlers, David Wilder, is very clear about the situation on his website: “This is a war, and at war you can’t have rules. Nazis neither followed rules”.

Not all settlers are orthodox Jews. One of the biggest settlements, Ariel, which has 16.000 inhabitants, is now a little town where religious rules are not so present as in other places. But even in the smallest settlements you’ll find families that have a much better reason for living there than the contract between God and Abraham: the rent.

Immigrants

Mali is around forty years old and has spent already five in Kedumim. How did she end up in this strange spot? “I lived in United States when I married a Sephardi Jew. He decided to emigrate to Israel and I converted to Judaism. First we tried to live in Herzliya – a town near Tel Aviv – but the the rent of the flat was around a thousand dollars a months, far too much for us. Here I pay not more than 150 dollars”. Mali doesn’t believe in the Promised Land nor in other divine rights. “I put up my workshop in a Palestinian village some three miles away” says Mali. “I’m used to live between the fronts”.

But if the Government decided to evacuate Kedumim, Mali knows very well what to do. “I’d take the kids and go to live to the other side, where I’d ask for Palestinian citizenship”. Mali has four children but she divorced from her husband – who became more and more orthodox – one year ago. Her house is a small pre-fabricated cage with a living room, two bedrooms, a kitchen and a board full of books in Hebrew and English. It is also the social center for the teenager girls from the neighborhood who know that they can have a couple of beers with Mali and smoke some cigarettes. The strip is Kedumim’s socially lower quarter. Here, nobody would speak out about God’s contract on the Land.

“Ideology? That’s the last thing we care about” says Rachel H. “My father is an Afghan Jew, my mother is an Australian convert. Kedumim is just about the only spot where we can pay the rent. To be fair, we don’t even pay it but nobody will throw us out”. Rachel left home when she was 18 and went to live to a kibbutz in North Israel. She comes back seldom as she hates the settlement in a general way and the religious prudery in particular.

“They would look very bad at you if you wear trousers. An ankle-long skirt and long sleeves down to the elbow, that’s the rule. There is no mixed school, not even in the kindergarten. And the swimming pool has different entry hours for men and women. Anyhow, with the kind of men you’d find here…” Her best friend, Sara D., corroborates her view. Also she thinks of Mali’s house as of a safe shelter: it’s about the only place she can meet her boyfriend . Because Yussef is Palestinian.

Love between the guns

Sara D. is 25 years old and pursues Psychologist studies in Ariel, one of the biggest settlements of West Bank. “I met Yussef at Mali’s place” she tells, “as he had come to repair the pipes. My father is the only one who knows that we are dating. If the neighbors found out about, nobody would speak any more to my sisters in school nor to my mother when she goes shopping”. Sara is living between the fronts and the crossfire comes sometimes as a stone which hits at night her car’s windshield.

«The settler called a Palestinian friend and the boy came with four friends to help him change the tyre»

She would tell it in a matter-of-fact way. “I survived because I was driving very slowly. Yussef has had a similar incident, as also the Jews throw stones on the Palestinian’s cars. But not all people are the same. A few days ago, a guy from Kedumim got a flat tyre in the middle of the night. He called a Palestinian friend with his mobile phone and the boy came with four friends to help him change the tyre. The Israeli soldier patrolling there couldn’t believe his eyes”. Anyhow, Sara is going to leave Kedumim as soon as she gets a visa to go with Yussef to France.

Mali, on the other hand, crosses the fire line every day. Her workshop, full of machinery, wood and paint, is like a second home to her. She shares all the business with Nasser, a 30-years-old Palestinian who has got a degree in Fine Arts, but prefers to work with the wood. There is no bitterness in his words when he traces an abstract of the situation: “We are trapped. Nablus is only ten miles away, but it is surrounded by Israeli troops. You can’t enter with the car. Crossing the hilltops on foot, you sometimes manage to get through. Last time I tried, the soldiers caught me and kept me for five hours. I think I won’t go any more”.

Around 15 miles west from Jinsafut, the Green Line separates Israel from the Occupied Territories, but no Palestinian can cross it since the Second Intifadad started in September 2000. “And you can’t go to Jerusalem neither. If they catch you, you’ll get six months in jail. That is, if you have got no points in their black list. If you have, they’ll jail you a year or two”.

“Gilad shot everybody he saw; since they killed him we are a little more relaxed here”

Settlers may feel themselves surrounded by the ‘Arabs’, but Palestinian are also besieged. From Nasser’s village you would see Kedumim at east, the Qarne Shomron, Nofim and Sakir settlements at west, Immanuel in the south and the military outpost of Qarnein in the north, where some families are already establishing prefabricated houses. There is real danger. “If there is suicide attack in Jerusalem or Tel Aviv, the settlers become very trigger-happy. In the last months, four men have been killed in this zone, two near Kedumim and two near Qarne Shomron, for no other reason than for being Palestines”, says Nasser. He remembers the murder of Gilad Zar with not so bad feelings. “Gilad shot everybody he saw; since they killed him we are a little more relaxed here”, he says.

Paramilitary Forces

The Israeli law converts the settlers into a paramilitary force: the military order 1456, issued on June 11th, 1998, grants the ‘civil guard forces of the settlers’ the right to ‘assist the occupation forces in their security activities outside the settlement’. The order 1457, issued the same day, allows them to ‘arrest, inspect and use force outside the limits of the settlements’ away from the supervision and control of the troops.

The result is a society which can only be called an apartheid regime. The hundreds of military check-points disrupt the traffic on all roads but only affect Palestinian cars, indentified by their green number plates. The yellow-plated cars, driven by settlers, would cross over to the left lane and pass the check-point immediately.

This rules are essential for Israeli economy. That is at least Mali’s view: “If they had all the same rights, you would be paying the Palestinians the Israeli minimum wage: 16 shekel an hour. Now they can pay them 10 shekel or 12, at maximum. No contracts, no taxes paid, no social security. On the paper, the Palestinian employees do not exist. I use to call that slavery, as in the Middle Ages”.

«On the paper, Palestinian employees don’t exist. I call that slavery, as in the Middle Ages”

In fact, Kedumim couldn’t probably exist without he Palestinian labour. Palestinians work in the Industrial park where they process soap or shoe-shining products or handle the machines that shape little plastic cups. They are also employed at the gas station at the entrance of Kedumim. They lay bricks and carry concrete in every single one of the many new houses under construction, including the new synagogue. Every morning, a group of men gathers at a crossroad watch tower and wait for a car to take them to the building places. Some even cover their heads with the red-and-white keffiya, the intifada’s symbol. They are not seen as traitors by the rest of Palestinians: everybody understands that first comes the bread of your family, then politics.

Boycotting settlers, not Jews

Inside Israel, not too many people support clearly the settlements, but even less oppose openly this colonization strategy of the Occupied Territories, condemned by dozens of United Nations’ resolutions. Not a single one of the mayor political parties suggests evacuation. Only Gush Shalom, the Peace Block Movement, asks on its webside (www.gush-shalom.org) to boycott the goods produced in the settlements. That is a very long list: the cheap labour force and the low taxes – Kedumim’s Industrial Park has even been declared ‘Development Zone Priority A’ – make investment attractive for many enterprises.

The most famous one is doubtless the beauty products manufacturer Ahava. Their facial treatment salts, won from the Dead Sea muds, are sold by catalogue all over Europe. The manufacturing center is located in the middle of the Palestinian territory and the nearby built settlement Mitzpe Shalem, were part of the Israeli workers live, is protected by fences and a door which only opens with a distance device controlled by its inhabitants.

“We are quite radical” says 72-years-old Judith Blanc. “We defend International Law»

Fruits are another export article. The settler David Menkin grows a vineyard with 4000 trees – “that’s cabernet-sauvignon variety” he says proudly – on one of the slopes of Kedumim. No Palestinians pick the grapes, only a group a pupils from the religious school, led by their rabbi Shaul Stern. The grapes are sent to the cellar of the industrial park of Barkan, another settlement, where they will be processed.

The ultimate destination of the bottles, with the words ‘Made in Israel’ on the etiquette, may well be an European store. But not always they get through. “Israel’s activities in Gaza, West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights are illegal” remembered European Commissar Chris Patten on May 15th, 2001 to the Parliament in Strasbourg, “and when goods manufactures in these zones are presented as of Israeli origin, customs officers cannot share this interpretation”.

That means, they will ask for the customs tariffs which true Israeli goods don’t need to pay. During the first year of the Customs Agreement between the UE and Israel, the European authorities refused more than 2000 certificates. This measure means a loss of around 200 million US dollars for Israel’s economy, around 1 percent of the total cash flow. But far more important is the symbolic value of the measure.

Symbolic is also the protest which takes place every friday noon in Jerusalem. Around thirty aged women, all clad in black, gather on the Paris Place carrying signs which read Stop Occupation in English, Hebrew and Arabic. “We are quite radical” says 72-years-old Judith Blanc. “We defend International Law. But we are not too many. All over Israel we may total 2000 people”. A few steps away from the silent demonstration, some young men who wear the blue Likud shirts hold up their own signs which read Arabs go out. They spit on the old women opposite.